From the ground, northeastern Norway might look like fjord country, peppered with neat red houses and dissected by snowmobile tours through the winter. But for pilots flying above, the region has become a danger zone for GPS jamming.

The jamming in the region of Finnmark is so constant, Norwegian authorities decided last month they would no longer log when and where it happens—accepting these disturbance signals as the new normal.

Nicolai Gerrard, senior engineer at NKOM, the country’s communications authority, says his organization no longer counts the jamming incidents. “It has unfortunately developed into an unwanted normal situation that should not be there. Therefore, the [Norwegian authority in charge of the airports] are not interested in continuous updates on something that is happening all the time.”

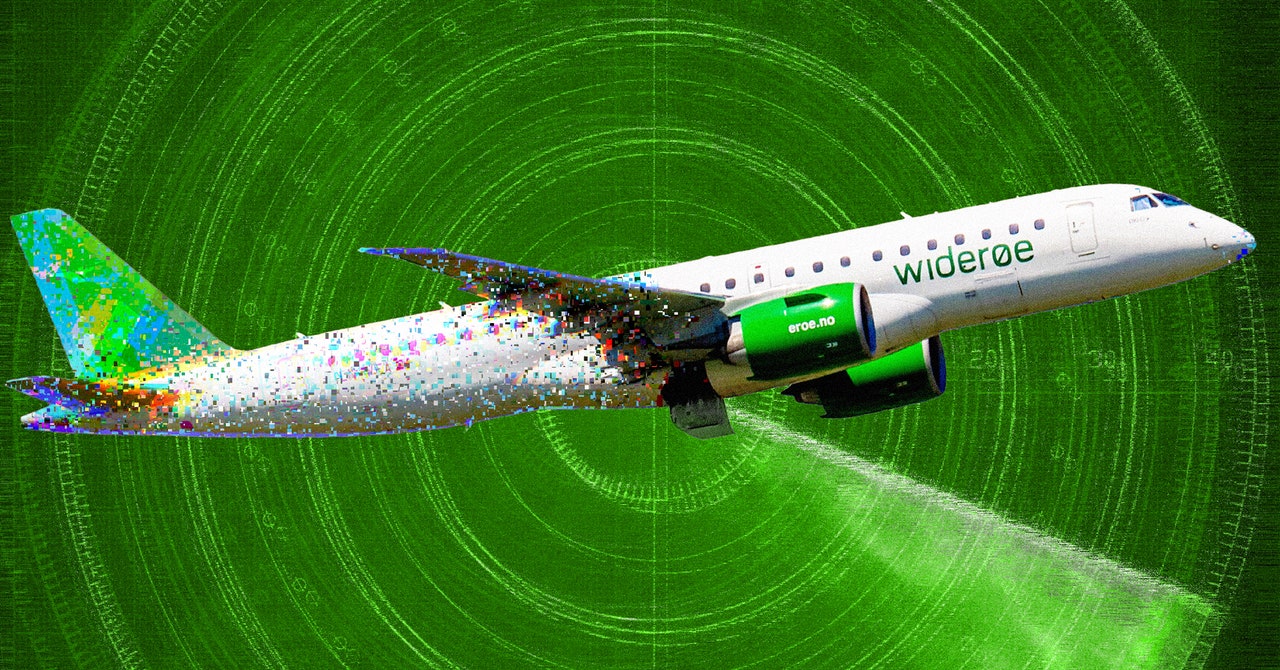

Pilots meanwhile, still have to adapt, usually when they are above 6,000 feet in the air. “We experience this almost every day,” says Odd Thomassen, a captain and senior safety adviser at the Norwegian airline Widerøe. He claims jamming typically lasts between six and eight minutes at a time.

When a plane gets jammed, warnings flash on cockpit computers and the GPS system used to warn pilots of a potential collision with terrain, such as mountains, stops working. Pilots are still able to navigate without GPS if they can communicate with ground stations nearby, explains Thomassen. But they are left with an eerie sense they are flying without the support of the latest technology. “You’re basically [going] 30 years back in time,” he says.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, jamming has dramatically increased across Europe’s eastern edges, and authorities in Baltic countries openly blame Russia for overloading GPS receivers with benign signals, meaning they can no longer operate. In April, a Finnair plane trying to land in Tartu, Estonia, was forced to turn back 15 minutes before landing because it could not get an accurate GPS signal.

Over the past decade, GPS systems have been considered so dependable that many smaller, more remote airports have started to rely on it completely instead of maintaining more expensive ground-based equipment, says Andy Spencer, a pilot and international flight ops specialist at OpsGroup, a member organization for pilots and others in the airline industry.