A report from the National Audit Office (NAO) today says we still do not know the full extent of the cladding scandal and it is likely to be at least 10 years before the problems are fixed.

While remediation works on most tower blocks over 18 metres with the most dangerous form of cladding are now complete or nearing completion, the scale of the cladding crisis has widened and mid-rise blocks (11 to 18 metres) are now being addressed. However, this means that up to 60% of buildings in England with dangerous cladding have not yet even been identified, the NAO says.

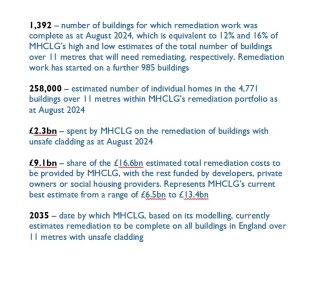

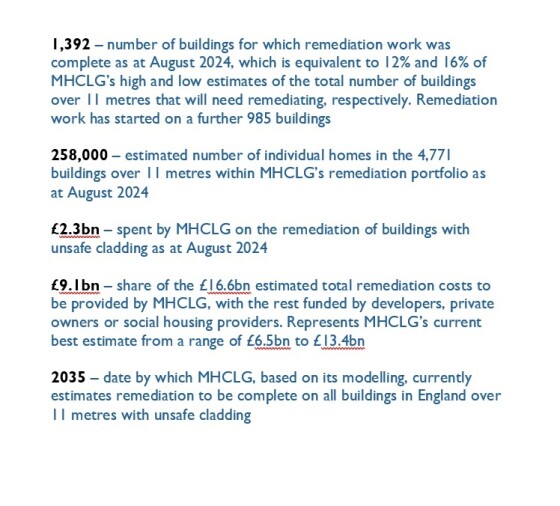

Across England alone, as many as 12,000 buildings above 11 metres have unsafe cladding, the NAO report says. At best, just 16% of these have been fixed.

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (MHCLG) modelling indicates an end date of 2035 for completing cladding remediation but, without published milestones, residents have no idea when their building will be made safe.

The National Audit Office recommends that MHCLG publishes a target date for the completion of remediation works and provides greater transparency on remediation performance.

The NAO’s report, Dangerous cladding: the government’s remediation portfolio, follows the publication of the Grenfell Inquiry report in September, which examined the root causes of the fire in June 2017 that resulted in the deaths of 72 people.

The NAO examines how well MHCLG is tracking down unsafe buildings, driving progress with remediation works and managing costs.

The government has changed the types of buildings within scope for its funding programmes, and its approach to remediation, as the scale and impact of the cladding problem became clearer. It now has programmes to address dangerous cladding for all the estimated 9,000 to 12,000 buildings over 11 metres in height that it considers need remediating.

So far, 4,771 buildings have been brought into the portfolio, but it is taking longer than expected to identify the remainder, and some may never be identified. With a potential 7,200 buildings or more (up to 60%) still to be identified, many people still do not know when their buildings will be made safe, the NAO says.

While building owners are responsible for fixing their buildings, engagement with government’s grant programmes is voluntary. As the NAO previously reported in 2020, incomplete building records, construction materials that differ from those on plans, and difficulties tracing owners can make identifying affected buildings difficult.

Seven years after Grenfell, 98% of estimated high-rise buildings (over 18 metres) with dangerous cladding are in the portfolio. Mandatory registration of high-rise buildings under the Building Safety Act 2022 is helping to identify any that remain. There is no mandatory registration for (more numerous) medium-rise buildings (11 to 18 metres). The government recognises that some building owners may be reluctant to engage with the programme for fear of uncovering problems that are out-of-scope for government funding.

Of the 4,771 buildings in the government’s portfolio – the equivalent of 258,000 homes – remediation work has yet to start on more than half. Work is in progress for a fifth, with around one third complete. Of all 9,000-12,000 potentially in scope, work is complete for only 12-16%, the NAO report says.

The report finds that, in total, it will cost an estimated £16.6bn to fix unsafe cladding on all buildings over 11 metres in England. MHCLG expects to provide £9.1 bn of this, with the remainder funded by developers who have agreed to remediate buildings they developed, private owners or social housing providers.

To keep taxpayer contributions within a £5.1bn cap over the long-term, MHCLG plans to recoup £700m through refunds from developers for remediation works that the taxpayer has already funded, and around £3.4bn from the new building safety levy. The levy will be paid by developers on new developments, though MHCLG is yet to confirm payment mechanisms. It does not expect to introduce the building safety levy until autumn 2025 at the earliest.

MHCLG acknowledges there may be overlaps between its remediation programmes and wider government priorities, from decarbonisation to building new homes, and the NAO report found MHCLG needs to do more to ensure that policies are not working at cross-purposes.

Gareth Davies, head of the National Audit Office, said: “Seven years on from the Grenfell Tower fire, there has been progress, but considerable uncertainty remains regarding the number of buildings needing remediation, costs, timelines and recouping public spending. There is a long way to go before all affected buildings are made safe, and risks MHCLG must address if its approach is to succeed.

“Putting the onus on developers to pay and introducing a more proportionate approach to remediation should help to protect taxpayers’ money. Yet it has also created grounds for dispute, causing delays.

“To stick to its £5.1bn cap in the long run, MHCLG needs to ensure that it can recoup funds through successful implementation of the proposed building safety levy.”

Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown MP, chair of the House of Commons public accounts committee, said: “Seven years after the tragedy at Grenfell, many residents are still in the dark about when their homes will be made safe. Remediation work is yet to begin on half of the buildings known to have unsafe cladding. Many buildings with dangerous cladding have still not been identified.

“The programme is falling behind schedule and MHCLG needs to pick up the pace to get it back on track. There is a long road ahead to resolve the cladding crisis and the government must take steps to better protect the taxpayer. It urgently needs to ensure its fraud controls are working and that developers contribute their fair share to the costs.”