When Kamala Harris stepped in to replace the tottering Joe Biden atop the Democratic ticket, there was no small amount of trepidation within her party.

The only basis many had for judging Harris was her performance as vice president, which was shaky before she hit her stride some years into the job, and the crash-and-burn campaign she waged for president in 2020, which flamed out long before any votes were cast.

Harris quickly allayed those concerns, at least among fellow Democrats. Her charismatic campaign style has shined through at rallies attracting capacity crowds. She headlined a boffo political convention in August and easily bested Donald Trump earlier this month in their one, and possibly only, debate.

Still, the hangover from her failed 2020 campaign lingers, owing to Harris’ leftward lurch and the position she took on issues, such as healthcare and immigration, that Trump and other Republicans have eagerly used to portray “Comrade Kamala” as the ideological stepchild of Karl Marx and Chairman Mao.

Polls show that one of Harris’ greatest weaknesses in this snap presidential campaign is a perception that she is “too liberal,” as nearly half the respondents stated in a recent ABC/Ipsos survey.

What’s striking is that Harris has never been the flaming lefty her positioning in the 2020 campaign would suggest, or some might impute from her grounding in the progressive climes of San Francisco, where Harris started her political career by winning election as district attorney.

“She’s center-left,” said Dan Morain, a former Times staff writer and author of the biography “Kamala’s Way: An American Life.”

“That’s what she was in San Francisco. That’s what she was when she ran for [state] attorney general … She’s a prosecutor,” Morain said, and while prosecutors aren’t necessarily conservative “by and large they’re more conservative than run-of-the-mill Democrats.”

It was political expediency — or, as some close to Harris prefer, necessity — that caused her to stake her leftward ground.

One Harris advisor, who has known the vice president for years, described the 2020 Democratic primary as a series of ideological litmus tests and a competition to see how many of the liberal boxes the large field of jostling candidates could check. The advisor agreed to speak candidly in return for anonymity, to preserve his relationship with the Democratic nominee.

“If you checked those boxes,” he said, “you could live to see another day.”

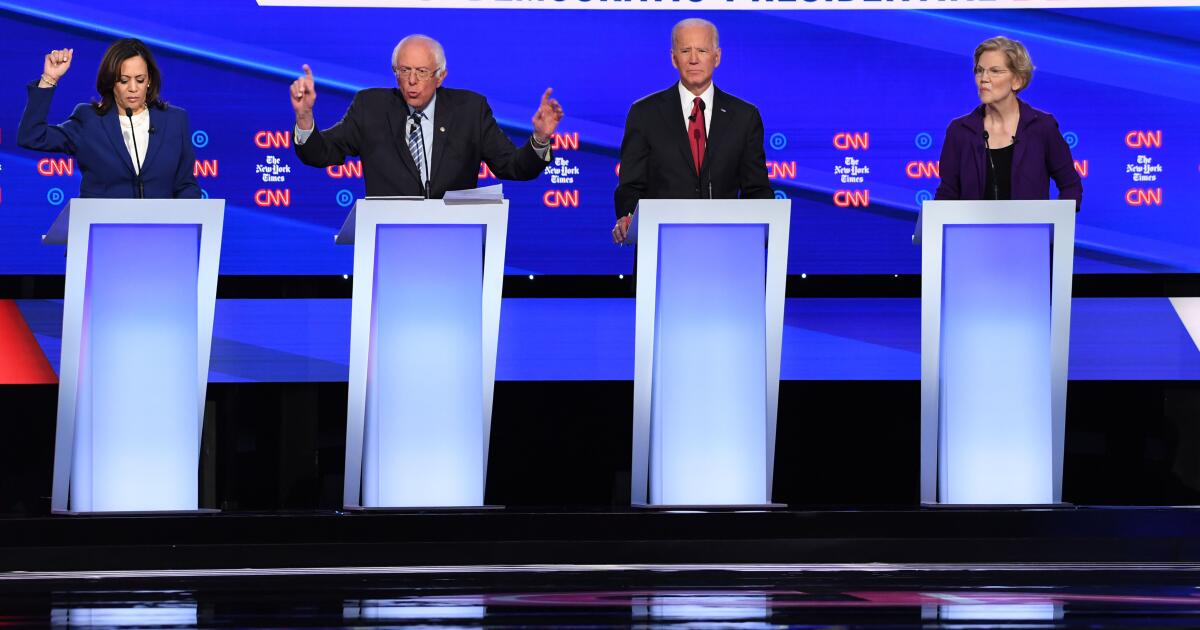

Another longtime member of Harris’ political circle, who was similarly circumspect in discussing her 2020 campaign, said “there was a perception that the path to the nomination was only through running on the left” and managing to “out-Bernie” and “out-Warren” the competition. (That would be progressive totems Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.)

That move not only turned out to be a strategic miscalculation, as pandemic-panicked voters turned to the more centrist Biden, but for Harris it was a masquerade. She was trying to be something she was not, this other longtime observer said. Worse, “She ended up adopting a bunch of positions that ultimately left her nothing but baggage four years later.”

Funny how that works.

As part of her makeover, Harris backed elimination of the country’s private health insurance system, supported a ban on fracking, called for drastic cuts to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency and said she was open to a “conversation” on allowing violent felons to vote from their cells. Recently, CNN’s Andrew Kaczynski surfaced a 2019 ACLU questionnaire in which Harris supported taxpayer funding of gender transition surgeries for detained immigrants and federal prisoners.

Harris has long since jettisoned those positions on healthcare, immigration and fracking. She abandoned her stance on jailhouse balloting the very next day. In response to Kaczynski’s sleuthing, the Harris campaign offered this response, a masterwork of opacity: “The Vice President’s positions have been shaped by three years of effective governance as part of the Biden-Harris Administration.”

As for Harris, she’s acknowledged changing some of her positions but insists, “My values have not changed.”

But her political persona certainly has. After running away from the image of a tenacious prosecutor in the 2020 race — when criminal-justice reform was a hot issue for many Democrats — she’s now making law and order a centerpiece of her White House bid.

There’s obviously a big difference between running in a primary, when a party’s most ideological voters hold sway, and campaigning in a general election, which requires appealing to a broader slice of Americans. Harris has benefited greatly from her overnight installation as the Democratic nominee, which spared her the need to genuflect so conspicuously to the political left.

But given her willingness to do that the last time she ran for president — even if it meant going against her more-centrist inclinations — voters aren’t wrong to wonder where Harris stands and how firmly she’ll stick to those values she professes to hold dear.

In 2002, as a U.S. senator from New York, Hillary Clinton voted to give President George W. Bush the authority to invade Iraq. It seemed, at the time, a politically wise move for someone considering a future run for president and wanting to avoid the weak-kneed image that had plagued Democrats since the Vietnam War era.

As it turned out, Clinton’s vote was a key reason she lost the Democratic nomination in 2008 to then-Sen. Barack Obama, a staunch opponent of the Iraq War.

All of those candidate contortions bring to mind a line from Hamlet: To thine own self be true.

It’s a good prescription for life. And for politics as well.