Homicide is a serious problem that calls for effective policy responses built on accurate information. Unfortunately, prominent politicians are again propagating the inaccurate notion that immigrants disproportionately contribute to crime, especially murder.

An Immigration and Customs Enforcement response to a request from a Texas congressman informed — or misinformed — many of the latest claims of a connection between immigration and violent crime. One statistic from the letter in particular has been in the headlines: ICE counted 13,099 cases of “non-detained” immigrants convicted of homicide.

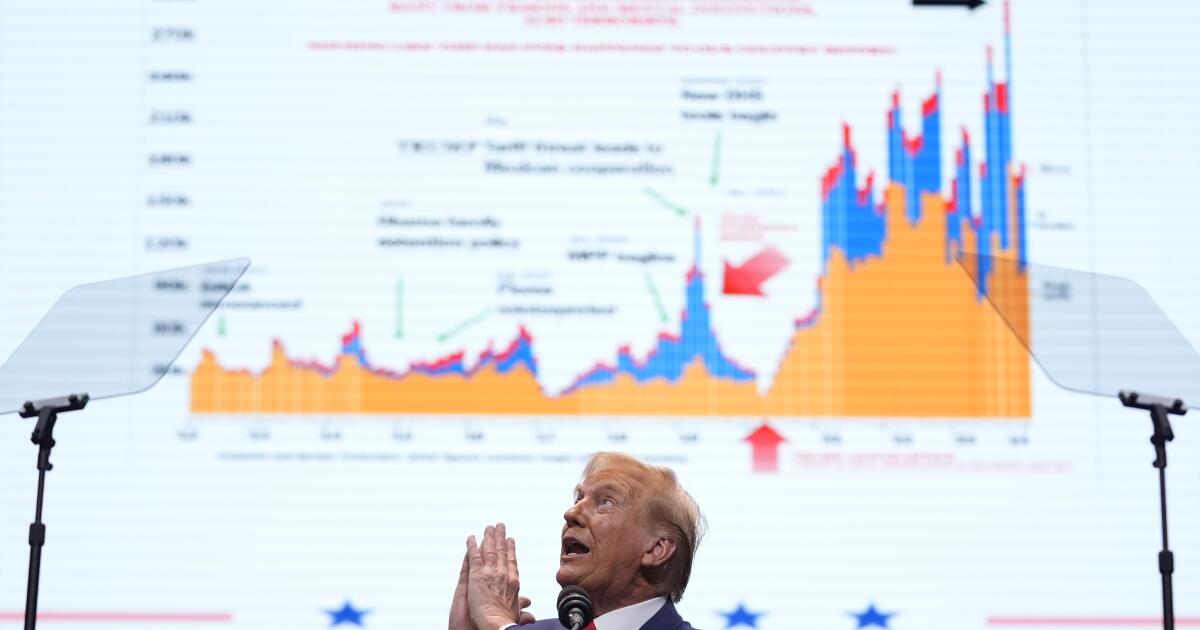

The implication that some seized upon was that thousands of immigrant murderers are roaming America’s streets and that the Biden administration is to blame. Former President Trump tied the figure to Vice President Kamala Harris on social media, writing: “It was just revealed that 13,000 convicted murderers entered our Country during Kamala’s three and a half year period as Border Czar.”

None of which is true. “Non-detained” simply describes individuals who are not currently in ICE’s custody; it doesn’t mean that they are free and able to do as they wish.

The bulk of these convicted murderers are assuredly serving their sentences in jails and prisons, with deportation awaiting them if and when they’re released. In addition, these cases accumulated over multiple presidential administrations — dating at least to Reagan — not just over the last four years.

ICE may not know when an individual is in a state prison. Moreover, the people on the agency’s non-detained docket may have had pending immigration cases for years — for example, because they were ordered deported to a country that is not cooperating with the United States. Or they may have never come into contact with ICE because Border Patrol officials released them before learning of a prior conviction.

Why would ICE ever release a noncitizen with a prior conviction as serious as homicide? The answer lies in the Supreme Court’s 2001 ruling that immigrants subject to deportation orders can’t be detained indefinitely by U.S. officials. That becomes relevant if an immigrant’s country of origin won’t cooperate with the United States.

So if an immigrant who is in the country illegally was sentenced to prison for homicide in 1980, completed the sentence in 2000 and was then ordered deported to a country that is not cooperating with the United States, that person must be released pending deportation.

The problem, then, is not that countless noncitizen murderers are lurking in the shadows across America thanks to the Biden administration’s negligence. It’s the long-standing lack of coordination between ICE and a variety of other agencies and entities, ranging from county sheriffs to foreign governments. It’s also the disingenuous use of ICE’s data to generate fear of immigrants.

In reality, research shows that immigration does not significantly contribute to crime. As a recent Cato Institute report highlighted, immigrants consistently commit less crime than their native-born counterparts. Cato’s study, which focused on Texas, concluded: “The conviction and arrest rates of illegal and legal immigrants … were lower than those of native-born Americans for homicide and all crimes.”

Tethering migration to murder not only creates an inaccurate impression of immigrants; it also wrongly suggests that violent crime is out of control more broadly. In fact, violent crime has remained at historical lows for the last two decades, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Homicides rose steeply in 2020 and 2021 but have since declined steadily. Murder remains a relatively rare event in this country: In a given year, 15,000 to 20,000 homicides are committed in the United States, or about 1 for every 19,000 Americans. About three-fourths of U.S. counties typically experience no killings in a year, and of the remaining counties, most see one or two.

We should absolutely do more to reduce violent crime and murder. We also need immigration reform that takes heed of our history as a nation of immigrants as well as the need to maintain control of our borders. But these two problems aren’t really related to each other.

And if we’re concerned about untimely deaths, perhaps our focus should be broader. The risk of suicide is roughly twice that of homicide. About 30,000 to 40,000 Americans die in vehicle collisions every year. More than 50,000 died of flu-related causes during the 2017-18 flu season. And almost a million died of COVID-19 during the first two years of the pandemic.

Policymakers who want to keep Americans safe and healthy face a multifaceted challenge. Credible facts and accurate representations of them would be a great place to start.

Daniel P. Mears is a professor of criminology and criminal justice at Florida State University. Bryan Holmes is an assistant professor of criminology and criminal justice at Florida State University.