Back at the 2024 Oscars, the true winner wasn’t an actor or actress or director. It wasn’t even (just) Ken. It was an archetype. The two films that took home the most Academy Awards were the atomic-bomb drama Oppenheimer and the comedy Poor Things, and both pictures rode to that ceremony on the backs of one of cinema’s most enduring characters: the mad scientist. Despite their wild differences, the films’ joint success highlighted our timeless fascination with eccentric creators and the monsters that emerge from their labs. The Oscar went to (opens envelope) our nervous relationship with technology.

With all due respect to WWII dramas and Emma Stone satires, no genre has done more to unleash the mad scientist upon the world than the horror film. They are one of scary movies’ most famous characters, just behind the Final Girl and doomed quarterbacks. The two most iconic images of the silent era come from Metropolis (1927) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), both chilling stories about the havoc of evil doctors. A century later, the mad scientist continues to haunt our movies, even if the inventions themselves do not. “Today, many of the things that would once have seemed like horror-story fodder are scientific reality,” noted The Atlantic in 2014. “But still, as the boundaries of human knowledge are continually pushed, the trope of the mad scientist endures.”

It may have endured, but the meaning of the mad scientist has evolved as much as our views on science itself. A look at American horror’s most iconic mad scientists reveals a surprisingly volatile relationship between horror and academia in the United States. It’s a relationship that endures to the modern day. We may be living in an age of reason, but horror fans aren’t motivated by reason. After all, what reasonable person would pay money to willingly scare the crap out of themselves for fun?

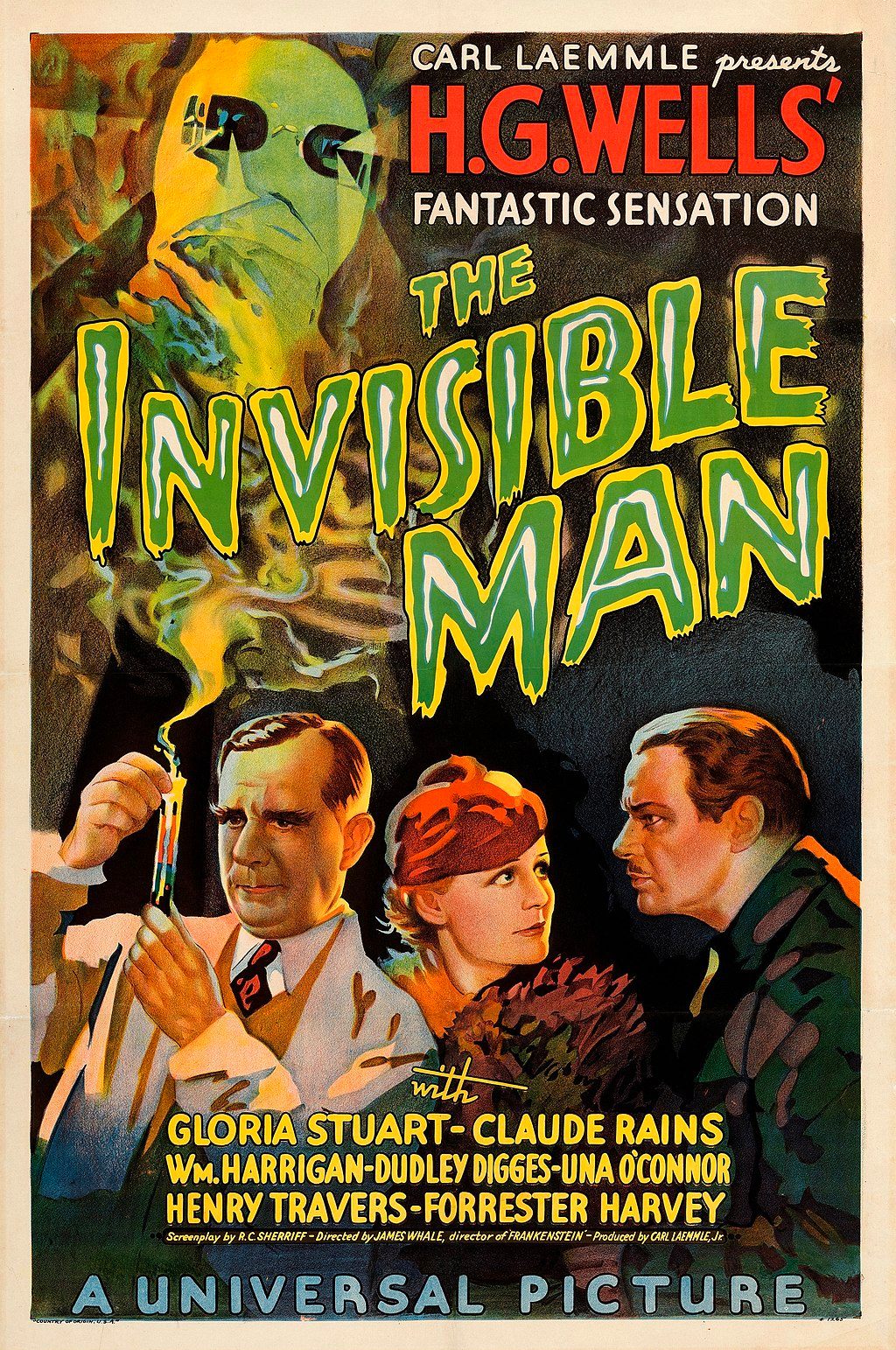

“He succeeds in impressing upon one the earnestness and also the sanity of the scientist.” This was, ironically, how a 1931 New York Times review first described cinema’s most notorious mad scientist: the titular doctor in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). Since the publication of that review, that “sane” doctor has become visual shorthand for experimental madness. But the “earnestness” hits on something critical about these first cinematic mad scientists. They were driven by a devout—if twisted—passion to harness the power of God. Sure, the passion came from different impulses. For Dr. Frankenstein, it was hubris (“I created it! I made it with my own hands!”). For the Invisible Man (1933), it was greed (“I realized the power I held: the power to rule, to make the world grovel at my feet.”). And for Dr. Moreau in 1932’s Island of Lost Souls, it was to freak out his dinner guests with weird questions (“Mr. Parker, do you know what it means to feel like God?”). But each of them were blurring the lines between science and religion. Made by filmmakers born when cinema felt like a kind of alchemy, this early era of mad scientists reflects a time where, for many Americans, science itself was considered a bit mad.

And in the 1930s, this was against the rules. Sometimes literally. Frankenstein was released just six years after the Scopes Monkey Trial put an academic on the stand for teaching evolution. According to horror historian Karina Wilson, this fear of science bled into movie houses, turning the mad scientist into a star. “That’s why Victor Frankenstein is seen as such a hubristic evil figure,” Wilson told NPR in 2020. “He’s not the hero of the movie. He’s the one who sets that terrible thing into motion.” So concerned was Universal about rocking the religious boat (or Ark?), they insisted on adding a warning to Frankenstein’s opening. (Incidentally, that warning was written by a young studio staff writer named John Huston. Based on everything I’ve read about Huston, penning something that cautious must have seriously pissed him off.)

Horror’s relationship to science grew more complicated as America marched into the 1950s and ’60s. An era of both postwar industrial optimism and the terror of Sputnik, scary movies became less eager to portray scientists as simple maniacs. Instead, the Eisenhower era’s most terrifying horror films, motivated by Cold War nuclear anxiety, were the ones where the monsters (or the Living Dead or the Body Snatchers) seemed to emerge from nature as suddenly and violently as a mushroom cloud. Japan’s nuanced Godzilla (1954) tried to remind us that those mushroom clouds were man-made. But U.S. distributors notoriously re-edited many of those pesky Hiroshima allusions from the domestic cut, because, America. In this period, scientists with plans “just crazy enough to work” were (momentarily) promoted from madmen to America’s “only hope.” (Oppenheimer himself got the cover of Time for “winning the war.”) In Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), for example, the dashing and shirtless Dr. David Reed (Richard Carlson) saves his companions using his genius in…monster fish science? His expertise not only reveals the terrifying Gill-man’s weakness, it cements Reed’s status as cinema’s sexiest ichthyologist.

Of course, marine biology wasn’t truly sexy until 1975, when Jaws became one of the highest-grossing horror movies (or movie movies) of the decade. One of the blockbuster’s heroes is Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), an oceanographer whose scruffy beard suggests a young academic straight from Berkeley. Jaws sailed into theaters in the wake of Lyndon Johnson’s Higher Education Act, when a record number of Baby Boomers flocked to college campuses. Suddenly, the laboratories and libraries so gothically portrayed in earlier horror films were part of America’s everyday curriculum. Combined with the radical culture of 1970s college life, fear of progress (scientific or otherwise) now seemed absurd, close-minded, and, worst of all, lame. It’s telling that two of the most famous mad scientists of this period, Gene Wilder in Young Frankenstein (1974) and Tim Curry in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), are from satires. In a decade that effectively kicked off with the arrest of the Manson Family and ended with the arrest of Ted Bundy, mad scientists were a welcome escapist fantasy. Audiences were now afraid of Michael Myers from John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). He may move like a monster created by Dr. Frankenstein, but he scared ’70s audiences precisely because we knew he was not.

As this ’70s attitude butted heads with the Reagan-era capitalism of the 1980s, horror films discovered a new type of villain, this one motivated by profit. The mad scientist of James Cameron’s Aliens (1986) isn’t a scientist at all. It’s not even a person. It’s the faceless Weyland-Yutani Corporation, the business funding the film’s cosmic expedition. Weyland didn’t create the titular xenomorph that eats most of Ripley’s (Sigourney Weaver) team, but its capitalist motives to harness the aliens for money feel no less deranged than those of Dr. Moreau. In the Gordon Gekko years, mad science was simply a business venture. It’s a perfectly ’80s detail that the closest character Aliens has to a mad scientist is Paul Reiser dressed like a space-yuppie. “Those two specimens are worth millions to the bio-weapons division,” Reiser’s character says of the aliens. Apparently greed is good, even if deadly facehugging aliens are not.

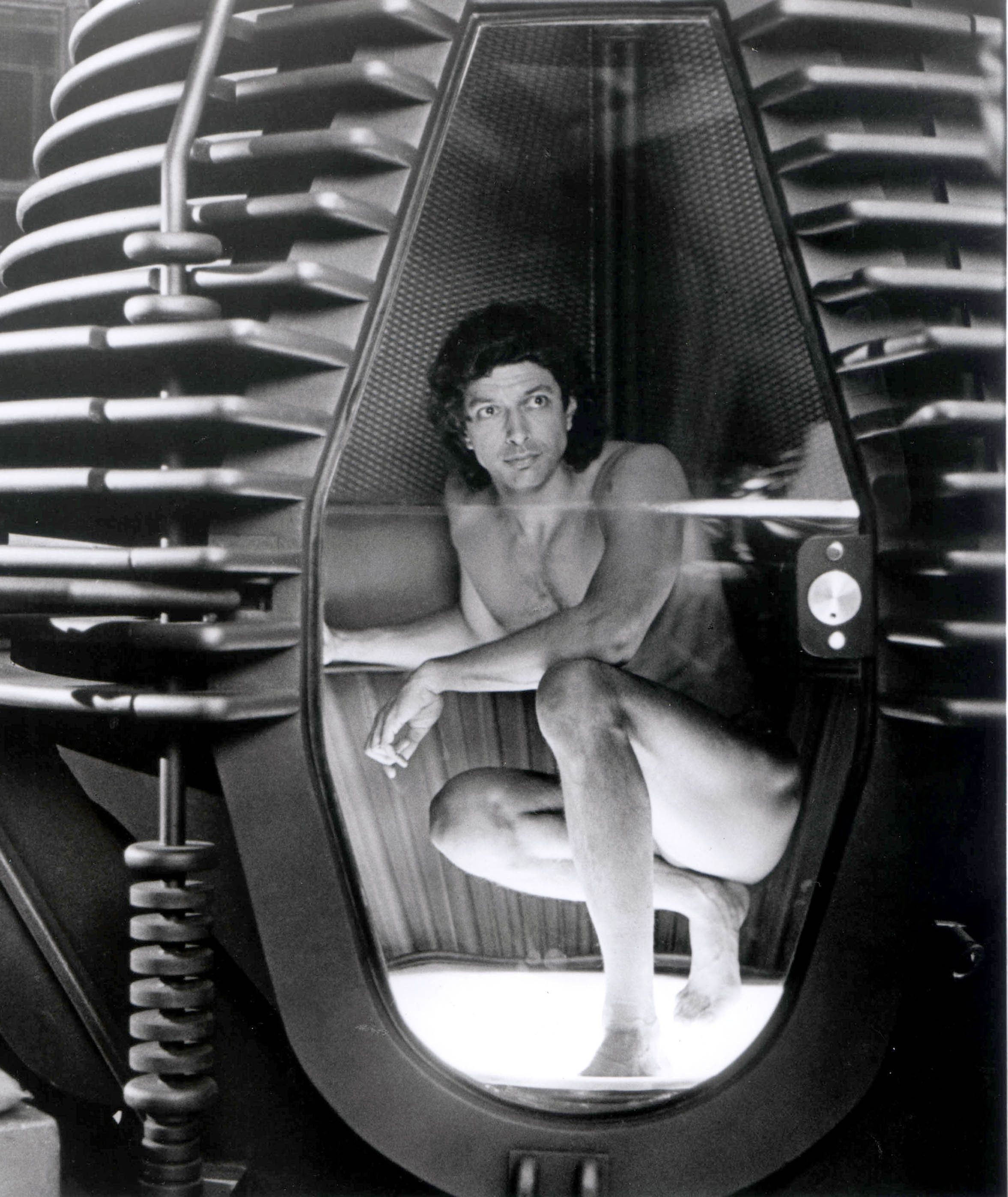

A similar corporate overlord funds the work of Dr. Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) in David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986), his teleportation research backed by the demanding Bartock Science Industries. Brundle admirably resists his investors, but his motivations include an equally-1980s trend: fame. In Cronenberg’s own MTV-era twist on the mad scientist, Brundle is not the typically reclusive genius. In fact, he welcomes the media. Made in a year when the closest thing we had to a science superstar was Mr. Wizard, The Fly feels predictive of our future wave of vain, self-proclaimed “disruptors.” It’s why Brundle allows a journalist (Geena Davis) to chronicle his research, why he asks her to videotape his teleportations with a big silver camcorder, and why he’s always flashing a red-carpet grin. Then again, he could just be grinning because, well, he’s played by Jeff Goldblum.

Computers exploded in the 1990s, so it’s surprising there weren’t dozens of horror films invoking mad computer scientists. This feels less like a failure of imagination than a reflection of the decade’s digital optimism. It’s hard to believe in our doomscrolling present, but in the early ’90s, people were genuinely excited about rapidly advancing technology (an enthusiasm that contributed to a dot-com crash at the decade’s end). A notorious exception is 1992’s Lawnmower Man, in which mad scientist Dr. Lawrence Angelo (Pierce Brosnan) conducts underground virtual-reality experiments on a simple-minded groundskeeper, turning his subject into an all-powerful cyber-god. A flop so maligned that Stephen King sued to have his name removed from it, Lawnmower Man is today most known for its primitive CGI depictions of virtual reality that answered the question: “What if your Trapper Keeper was a movie?”

If the mad scientists of the 1990s weren’t creating tech-demons, they were at least embracing the tech boom’s exhilarating attitude. In the underappreciated release Flatliners (1990), a group of medical students secretly conduct experiments into the afterlife by clinically killing and reviving each other. Unlike previous, grim forays into mad science, however, this macabre experiment is presented as an act of thrilling, Gen-X rebellion. The Dr. Frankensteins of Flatliners are played by the decade’s coolest young stars, including Keifer Sutherland, Kevin Bacon, and Julia Roberts (as an all-too-rare female mad scientist). It’s a lineup that makes Flatliners the Empire Records of challenging Natural Law. They’re radical, but in the skateboarder sense of the word. “Philosophy failed. Religion failed. Now it’s up to the physical sciences,” shouts Kiefer Sutherland’s med student, amped up on youthful angst. “Today is a good day to die,” he adds, sounding less like a scientist and more like Bodhi from 1991’s Point Break.

In the last decade, tech CEOs finally got the horror villain they deserved (sorry, Tim Robbins in 2001’s Antitrust). But after actual nightmares like Cambridge Analytica’s data mining, Russian social media influence, and Elon Musk, you know, just in general, our greatest scientific threats seemed like the selfish, politically motivated, and craven whims of the creators themselves. In Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014), Oscar Isaac is Nathan Bateman, an enigmatic tech billionaire who invents lifelike female robots. The film’s creature is an AI (Alicia Vikander), but the threat is Nathan’s obsession, which feels less like Frankenstein wanting to create life, and more like a predatory man eager to control women—an impulse confirmed in the film’s most iconic scene, where Isaac programs one of his female robots to join him in an impromptu disco dance. Three years later, Jordan Peele’s breakout Get Out (2017) would shift the mad scientist’s evil gaze toward race. In the film, Dr. Armitage (Bradley Whitford) secretly carries on his family’s sinister science of hijacking the brains of black kidnapping victims. Even the movie’s “sunken place,” seemingly created by Catherine Keener’s demented psychiatrist, is a form of mad science. Instead of a laboratory, all she needed was a teaspoon.

When theaters closed in the early days of our all-too-real horror that was the pandemic, back in March 2020, the number-one movie in America was The Invisible Man, a remake of the foundational 1933 mad scientist film. It’s a triumph that both versions were hits, but their depictions of the mad scientist are strikingly different. In the original, Claude Rains is driven mad by his invisibility serum. But in the 2020 remake, starring Elisabeth Moss as a terrorized wife, the Invisible Man was already an abusive husband long before he ever disappeared, a scenario even more terrifying. Does science drive men mad, or do mad men use science to weaponize their worst impulses? For horror films, maybe the scariest thing is that it’s both. The mad scientist deviously shifts its meaning. Like any great horror scare, we don’t know what angle they will attack from. It’s not a static character. To quote the original mad scientist: It’s alive.

Pat Cassels is an Emmy-winning writer, actor, and comedian who has worked at TBS’s Full Frontal with Samantha Bee and CollegeHumor. He has contributed to The New Yorker, Los Angeles Review of Books, Slate, and The New York Times Book Review, and received the Writers’ Guild of America award in 2020 and 2022.