In 1911, an aboriginal hunter named Ördek first came across what looked like a long sand dune full of protruding wooden poles, within the flat and barren desert landscape of Northwestern China’s Tarim Basin. In 1934, Swedish explorer Folke Bergman began excavations on the site, discovering a massive Bronze Age tomb. Guided by Ördek, Bergman uncovered 12 burial sites, naming the grounds Xiǎohé mùdì, or Little River Cemetery.

Afterwards, the site would go untouched for decades—slowly being reclaimed by the desert. In 2000, archaeologists from the Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology in Xinjiang, China rediscovered the Xiaohe cemetery. Between 2002 and 2005, the team excavated the extensive site, finding 167 tombs and numerous artifacts—including carved wooden poles in the men’s tombs, representing phalluses, and oar-shaped ones in the women’s, representing vulvas. One finding in particular, however, left the archaeologists stumped.

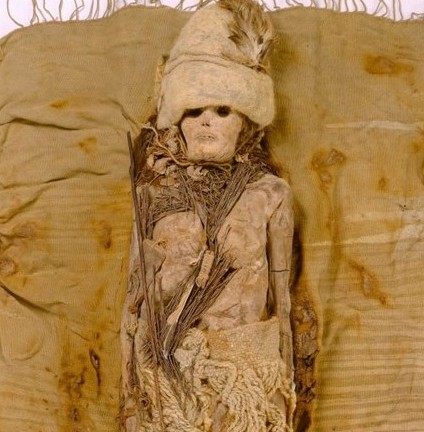

Several mummies, reaching up to 3,600 years old, had a mysterious white substance sprinkled on their heads and necks. This unknown substance, they posited, could be a type of fermented dairy. It is now known to be the world’s oldest preserved cheese, and its DNA is helping reveal historical mysteries.

Scientists have, for the first time, successfully extracted and analyzed DNA from this ancient cheese, reported a paper published today in the Cell Press journal Cell. “The history of fermented dairy is largely lost in antiquity, as both artifacts and molecular evidence of ancient fermented dairy are extremely scarce,” wrote the authors in their new paper. Thanks to the arid nature of the Taklamakan Desert, these cheesy morsels remained excellently preserved, making them perfect to examine for this study. “These samples are a rare opportunity,” says Qiaomei Fu, the paper’s corresponding author at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Researchers have long known that dairy was consumed across the Eurasian steppe—extending from Hungary to China—for millennia. Crops require intensive irrigation, while livestock thrive on the vast grasslands. Fermentation not only preserves dairy but also promotes gut health and reduces lactose for easier digestion. “We know that people were fermenting milk in order to make cheese, yogurts, and several other types of dairy products in the past, but which strains [of bacteria] they used in the past are still rather mysterious,” says biomolecular archaeologist Shevan Wilkin at the University of Basel in Switzerland, who was not involved in the study. Now, thanks to advanced DNA analysis, that mystery is beginning to unravel.

The dairy remains were identified as kefir cheese. To make kefir, people add lumpy white kefir grains, which are full of bacteria and yeast, to milk in order to ferment it. The grains act much like a sourdough starter, and adding them to milk results in liquid whey and clumpy kefir cheese curds. Samples from three different tombs were teeming with bacterial and fungal species, including Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens and Pichia kudriavzevii, both of which are found in today’s kefir grains.

There is a long-held assumption that kefir originated solely in the North Caucasus region of modern-day Russia, and spread from there. However, there is also early evidence of kefir in Tibet. After using DNA analysis to compare bacteria subspecies of the past and present, researchers found evidence supporting a second path for the origin of kefir production, starting in Xinjiang and spreading to other regions in East Asia, including Tibet. “The path is more complicated than what we think,” says Fu.

The samples were also found to have cow and goat DNA. Analysis showed the dairy goats of ancient Xiaohe belonged to a lineage that was widespread across Eurasia in the post-Neolithic period, supporting the idea of communication and exchange between Xiaohe and the steppe populations.

These discoveries don’t just teach us about the evolution of this kefir, but serve as a window into the lives of ancient humans. While we don’t know exactly how the taste would compare to today’s cheese, “it must have been okay, or else they wouldn’t go through the effort to make it,” says Fu. Whether it was prized for its taste or nutrition, kefir held great importance in Bronze Age China, especially since it was considered a snack worthy of accompanying the dead into the afterlife.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.