This article is adapted from the November 9, 2024, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

Walk into a church and you’ll likely find the usual iconography: Christ on the cross, a serene Virgin Mary, perhaps an angel or two. But in East Yorkshire, England, another figure joins these icons on a chapel’s decor: the turkey.

St. Andrew’s Boynton Church is the final resting place of the Strickland family, an aristocratic bunch based in Yorkshire. Its most famous member, William Strickland, was a British navigator who claimed to have introduced the turkey to England in the mid-1500s. This accomplishment is celebrated throughout the family’s chapel: Bibles sit atop a turkey-shaped lectern, a sculpted bird perches over a family memorial, and light filters inside through a stained-glass turkey window.

I have been obsessed with the turkey chapel ever since I learned about it a few years ago. Not only is it incredible for a waddling bird to take center stage in a church, but I’ve never seen the humble turkey get this kind of respect.

After all, the turkey gets a bad rap. When Ben Franklin suggests it as a candidate for the national bird in the musical 1776, it’s a punchline. And every Thanksgiving, there are turkey haters spouting the same gripes: It’s dry. It’s bland. It’s filler between show-stopping sides.

But I’m here to say the turkey deserves better. With the right preparation—I’m partial to Samin Nosrat’s buttermilk-brined roast turkey recipe—it can have the perfect balance of juicy meat and crisp, seasoned skin. And, in my opinion, it’s the best sandwich meat, always serving as a complementary team player with other fillings.

Beyond its flavor, however, the turkey has a long ceremonial history in North and Central America. Archaeological evidence in Guatemala suggests the Maya domesticated Meleagris gallopavo (a species also known as the Mexican turkey) as early as 300 BC. In the time since, the turkey has played a key role in rituals ranging from traditional dances to presidential pardons. Read on for some of our favorite turkey traditions. Hopefully, they’ll make you a bit more grateful for this big, beautiful bird.

Gods and Sacrifices

Turkeys played a key role in rituals among ancient Mesoamerican civilizations. In fact, the birds were likely first domesticated for ceremonial use before being bred for their meat. In 2018, researchers examined turkey bones dated to between 300 BC and 1500, from areas stretching from Northern and Central Mexico to Yucatán. They noticed that the bird’s remains were rarely found in domestic refuse and instead were excavated from temples and human graves.

In pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican codices, turkeys appear in the form of the god Chalchiuhtotolin, (or “jade turkey”) and are mentioned as part of Aztec ritual sacrifices. Highly valued, the birds were even among the gifts Moctezuma presented to Hernán Cortés before the conquistador betrayed him. Seeing the turkey for the first time, the Spanish thought it looked like a plain peacock and gave it the name pavo, a shortening of pavo real (“peacock”).

Turkey Dances

You can still see the ceremonial importance of the turkey in traditions like the Guelaguetza festival of Oaxaca, Mexico. The annual July event celebrates Indigenous cultures, with crafts, food, and lots of dancing.

In small parades known as calendas, performers hoist papier-mâché turkeys while bird-shaped figures shoot fireworks. Even the festival’s ritual dances celebrate the turkey as a revered gift, with performers often holding live birds or puppets while they whirl around.

Turkey Drives

917 Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

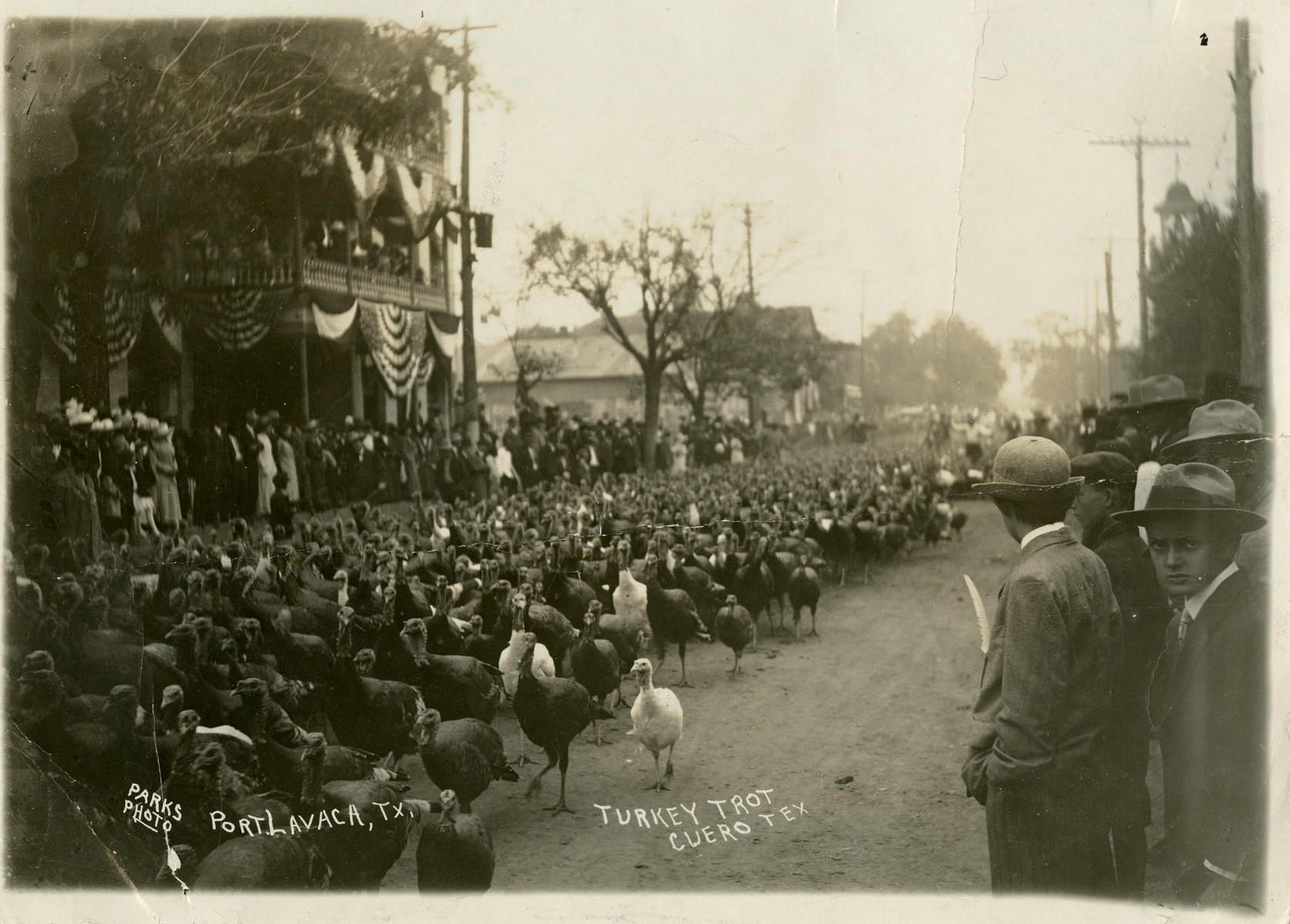

When you hear “turkey trot” now, it probably brings to mind those go-getters who, instead of sleeping in and watching the Macy’s Day Parade with a coffee or mimosa on their couch, choose to wake up early for a run on Thanksgiving Day. But at the first “turkey trot” in 1912, it was the turkeys doing the running.

A crowd of 30,000 attendees came to Cuero, Texas, to watch farmers herd flocks of 5,000 to 10,000 turkeys into town. The tourist event was recreating the bygone tradition of the turkey drive, when livestock owners would guide their flocks on the long journey from farm to market.

Dating back to the 17th century, turkey drives were an essential tradition in the age before refrigeration and trucks. Though herding turkeys came with its own unique challenges—such as the birds’ instinct to roost at the first sight of darkness, even if that darkness came from an artificial source like a covered bridge—the turkey was a fine long-distance walker. In her book More Than a Meal: The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality, Karen Davies writes, “The bird’s amiability, vigorous constitution, and long, strong legs made these drives possible.”

Turkey Pardons

Though Ronald Reagan was the first U.S. president to use the term pardon when sparing a turkey in 1987, the tradition of pardoning a bird at the White House may go back to Abraham Lincoln. According to a popular (and possibly apocryphal) story, the Lincoln family received a turkey as a gift for their Christmas dinner in 1863.

They didn’t count on Tad, the president’s son, adopting the bird as a pet. Tad named him Jack and trained the turkey to follow him around the White House. When it came time to slaughter Jack, Tad petitioned his father for a reprieve and received it—in the form of an official letter that Tad was able to show the head chef.

Today, a monument to this merciful moment stands in Hartford, Connecticut. Commissioned by the city’s Lincoln Financial Group, the turkey sculpture is part of a series commemorating the achievements of the firm’s namesake.

GPA Photo Archive / CC BY-ND 2.0

But just what happens to a turkey after it’s pardoned by an American president? For years, they were sent to Mount Vernon, but the practice was suspended when staff said the birds’ size disrupted the historical accuracy of the site: The 50-pounders were a far cry from the smaller birds of the 1700s.

The modern turkeys’ large size also means their post-pardon lives tend to be short. Bred to be plump and fattened with corn and soybeans, modern turkeys are too unhealthy to survive more than a few months past their pardon date.

This led to some depressing coverage in 2001, when ABC News visited Virginia’s Kidwell Farm, then the home for pardoned turkeys. “We usually just find ’em and they’re dead,” a farmer said, noting that one died within days of reaching the farm.

Today, the pardoned turkeys often head to agriculture or veterinary schools to receive care for the rest of their lives. Last year’s turkeys, Liberty and Bell, made a home at the University of Minnesota College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.