This story was originally published on The Conversation. It appears here under a Creative Commons license.

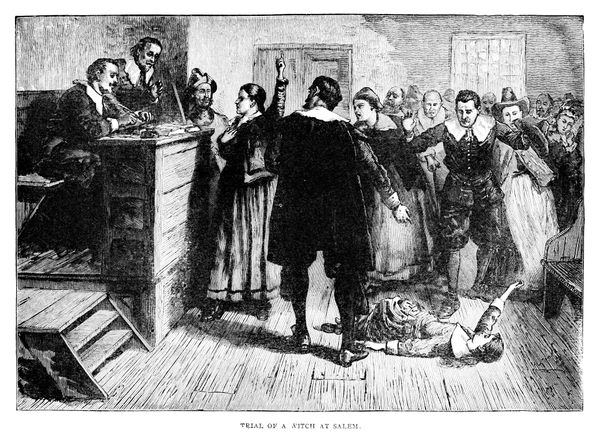

I teach a course on New England witchcraft trials, and students always arrive with varying degrees of knowledge of what happened in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692.

Nineteen people accused of witchcraft were executed by hanging, another was pressed to death and at least 150 were imprisoned in conditions that caused the death of at least five more innocents. Each semester, a few students ask me about stories they have heard about dogs.

In 17th-century Salem, dogs were part of everyday life: People kept dogs to protect themselves, their homes and their livestock, to help with hunting, and to provide companionship.

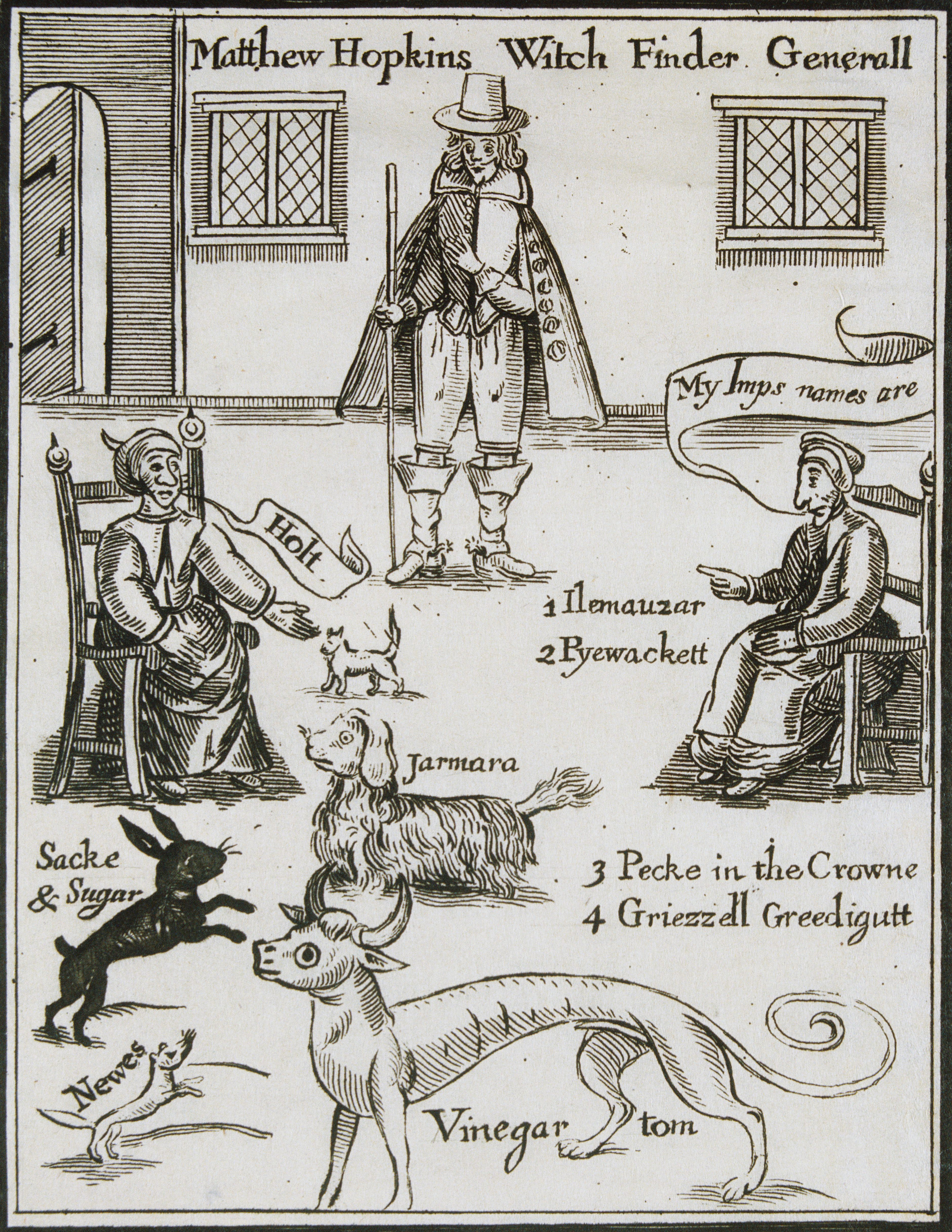

However, a variety of folklore traditions also associated dogs with the devil—beliefs that long predated what happened in Salem. Perhaps the most famous example of such belief is the case of a poodle named Boy who belonged to Prince Rupert, an English-German cavalry commander on the Royalist side during the English Civil War. Between 1643 and 1644, stories spread across Europe that Boy the poodle had supernatural powers, including shape-shifting and prophecy, that he used to aid his master on the battlefield.

There is no mention in the official records of Salem’s trials of any dogs being tried or killed for witchcraft. However, dogs appear several times in the testimony, typically because an accused witch was believed to have had a dog as a “familiar” who would do her bidding, or because the devil appeared in the form of a dog.

Numerous testimonies in the Salem trial records claim that dogs were in league with the devil, adding to the paranoia of this community that was spinning out of control.

On May 16, 1692, a 45-year-old Amesbury, Massachusetts, man named John Kimball testified against Susanna Martin, a 71-year-old widow, saying, among other things, that she had caused a “black puppy” to appear before him when he was alone in the woods. Kimball testified that he was terrified by the dog, which he thought would tear out his throat. The dog disappeared when he began to pray.

This, among other testimony, would contribute to Martin’s conviction for witchcraft in June 1692; she was hanged on July 19, 1692.

In several instances recorded by the courts, accused witches confessed that the devil had appeared to them in the form of a dog. In September 1692, 19-year-old Mercy Wardwell testified that she had been conversing with the devil, and that he had appeared to her in the shape of a dog. Her confession caused her to be jailed, although she was later released when the hysteria died down.

During the same proceedings that September, 14-year-old William Barker Jr. testified that the “shape of a black dog” appeared to him and provoked anxiety; soon after this, the devil appeared. It’s hard to know if he was suggesting that the dog was the devil himself or his companion. Barker confessed that he had “signed the devil’s book,” meaning that he had made a covenant with the devil and was a witch. Barker was jailed, though he would later be acquitted.

Tituba, a woman of color enslaved in the Rev. Samuel Parris’s household, also testified about a dog. When she was examined by magistrates on March 1, 1692, Tituba recounted how the devil had appeared to her at least four times, “like a great dog” and as “a black dog.” She also said she saw cats, hogs and birds, an entire menagerie of animals working for the devil.

Kimball’s, Wardwell’s, Barker’s and Tituba’s testimonies certainly may have contributed to the ongoing alarm that the residents of Salem were being led astray by a devil who might appear to them in the shape of a dog.

Some popular accounts of the trials also suggest that at least two dogs were killed during the trials, but there is no evidence supporting this in the official legal testimony of the time. There is certainly some local legend that supports the claim, and many accounts of Salem have included these two dog deaths as a part of the story.

According to local historical researcher Marilynne K. Roach’s 2002 book, “The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege,” some of the afflicted girls claimed that a man named John Bradstreet had bewitched a dog. Although the dog was a victim, it was killed. Roach’s history also notes that another dog was shot to death when a girl claimed that the dog’s specter had afflicted her. Witchcraft belief at the time held that witches could send their “spectres,” or spirits, out to do their bidding.

While these are compelling stories, neither of these events can be verified in any existing official trial documents. The source that Roach cites for the Bradstreet case is Robert Calef’s book “More Wonders of the Invisible World,” which was published in 1700. Calef, who was a Boston merchant, objected to how the trials were conducted. However, he was not present at the trials, and it is not clear what his source was for the dog stories. Such stories—and Calef’s uncited retelling of it—do not have the same authority as the legal documents in the case.

The earliest account of a dog being shot for being a witch appears in a commentary on the Salem trials, “Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits,” published in 1693, in which the clergyman Increase Mather claims that “I am told by credible persons” that a dog was shot for bewitching a person.

But significantly, Mather did not name the human victim or the person who told him the story. Surprisingly, Mather actually defended the dog, saying that the fact that they had successfully killed it meant that “this dog was no Devil.”

Nearly every history of Salem recounts how when Samuel Parris’s daughters were having terrible fits that led people to believe they were bewitched, Tituba, the enslaved woman who lived in the household, baked a “witch cake” using urine from the afflicted girls and fed it to the family’s dog. Somehow, this was supposed to cause the dog to reveal the identity of the witch. Indeed, Reverend Parris condemned the ritual, which itself seemed to be its own kind of witchcraft.

All around, Salem’s witch trials seem to have been bad for dogs. Although there is no official legal evidence that dogs were killed for being witches, it’s clear that there were strong associations between dogs and the devil, and that dogs were sometimes treated poorly because of superstition.

The Salem trials are a horrifying example of what happens when people use terrible logic and leap to indefensible conclusions with shoddy evidence. In an environment of fear and distrust, even man’s best friend could be suspected of dealings with the devil.

Bridget Marshall is a professor of English at UMass Lowell.